Michelle Ouinville

Arrived: July 3, 1668

Age at arrival: 21

Births: 7 / 5 surviving

Widowed: twice

Age at death: 53

Michelle Ouinville was our only Filles ancestor to arrive in 1668, but her story of resilience and strength would compensate for many. She was born about 1647 in Paris to a woman named Antoinette Bonnard and her husband Pierre Ouinville. When Michelle was 21 and after losing both parents, she was interviewed and accepted for passage to New France where she would be free to choose a husband if she found him desirable. And there would be many to choose from, she was undoubtedly told.

The ship La Nouvelle France, laden with cargo and 79 Filles du Roi, made a spring departure from Dieppe. Michelle brought her trousseau as her dowry with belongings which she stated to be worth about 400 livres. Compared to other trips made by French sailing vessels to Québec, this voyage was made in good time, spending just two months at sea and arriving in Québec City in early summer. However, unlike most Filles who remained there, Michelle decided to resume her passage to the ship’s next destination, Trois Rivières, where just 12 per cent of all Filles du Roi would venture to start their new lives. Here she would face her responsibility to accept the future without looking back. To do so would have been futile anyway.

Nicolas Barabé was also born about 1647. His place of birth is recorded as Quincampoix in Normandy, France. He was the son of Robert Barabé and Marie Tarou. Little more is known about his early life in the old country, but the official census of 1667 revealed his presence at Trois-Rivières where he was the servant-engagé of Étienne Seigneuret. He was just 20 years old at the time, but he might very well have been in Canada for several years. Or not.

Since most literature about the meetings that brought the Filles du Roi together with their spouses focuses on the large number who landed in Québec City — actually 70 per cent, we surmise that meetings with potential husbands were very similar at Trois-Rivières, the next port of call. How Michelle Ouinville vetted Nicolas Barabé and chose him for marriage will never be known, of course, but we do know that on October 21, 1668, notary Séverin Ameau drew up a marriage contract between them, both 21 years old, and neither could sign it. The couple consummated their marriage, received Michelle’s regal gift of 50 livres in kind, and settled in Trois-Rivières where they had five children. Four would survive their childhood years.

Until this point in her life, nothing was highly unusual for Michelle Ouinville, at least in the culture of early Québec. But in roughly May 1676, scarcely eight years after she had stepped off La Nouvelle France, Michelle became a widow when Nicolas Barabé drowned in a storm on the Saint-Laurent. She was just 29 years old.

Clearly women were a valuable commodity in New France, and as mentioned earlier, most widowed Filles appear to have remarried at record speed, often within weeks, sometimes within days. But the records reveal a contract drawn August 23, 1676 by notary Séverin Ameau in which Michelle, now widowed for several months, leased out three pigs, perhaps in an effort to raise money to feed her young children. Unlike others, she may have been far more discerning in whom she would choose after losing Nicolas.

Her youngest child, two-year-old Marie-Antoinette Barabé, would one day grow up and marry. And Marie-Antoinette would create a new family whose lines would lead directly to Clarice Bergeron.

- 1691 Marie-Antoinette

Barabé m. Louis Auger » Pierre

- 1734 Pierre Auger

m. Marie-Therese Rivard » Pierre [Jr]

- 1766 Pierre Auger [Jr]

m. Marie-Anne Melançon » Marie-Victoire

- 1801 Marie-Victoire Auger

m. Jean-Baptiste Croteau » Marie-Julie

- 1821 Marie-Julie Croteau

m. François-Xavier Bibeau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau

m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron

m. Lazare Côté

- 1691 Marie-Antoinette Barabé m. Louis Auger » Pierre

- 1734 Pierre Auger m. Marie-Therese Rivard » Pierre [Jr]

- 1766 Pierre Auger [Jr] m. Marie-Anne Melançon » Marie-Victoire

- 1801 Marie-Victoire Auger m. Jean-Baptiste Croteau » Marie-Julie

- 1821 Marie-Julie Croteau m. François-Xavier Bibeau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron m. Lazare Côté

Life was not over for Michelle Ouinville.

Somewhere among Trois Rivières’ 500 inhabitants was a man named Michel Lemay dit Le Poudrier. He was born about 1630 in Chêsnehutte-les-Tuffeau, in the French province of Anjou, the son of François Lemay and Marie Gaschet. He had been in Canada since about 1653 and in the Trois-Rivières area since 1654. Records divulge that on March 9, 1655, he was a party to a contract prepared by notary Séverin Ameau to clear an island near Trois-Rivières. Michel Lemay was a mature man and himself a widower. Eighteen years earlier, he’d married Marie-Madeleine Duteau in 1659 with whom he had nine children before her death.

Michelle Ouinville would become Michel Lemay’s new lifemate. On April 12, 1677, nearly a year after Nicolas Barabé’s death, notary Antoine Adhémar drew up a marriage contract between Michelle, now 30, and Michel Lemay, now 46, in the home of a friend at Batiscan. Neither spouse signed the contract, but Pierre Loiseau, future husband of an unrelated Fille du Roi, signed as a witness.

About a year after they married, Michelle and Michel moved with their large, extended family to Lotbinière where Michel Lemay owned a plot with six arpents of frontage (an arpent being about .8 of an acre) and worked as an eel fisherman. At that time a barrel of salted eels sold for 25 to 30 livres — a handsome sum in those days. Soon the couple had two more children, thus increasing the number of their shared progeny to a whopping 15.

While Michel Lemay had already named a daughter Marie-Madeleine Lemay from his first marriage, he and Michelle Ouinville gave their own firstborn the same name — unwittingly creating potential for serious confusion in future generations! It was precisely this daughter who would create a second genealogical connection from her mother Michelle Ouinville to Clarice Bergeron.

- 1695 Marie-Madeleine

Lemay m. Claude Houde » Simon

- 1735 Simon Houde

m. Marie-Madeleine Morisset » Madeleine

- 1764 Madeleine Houde

m. Jean-Joseph Croteau » Jean-Baptiste

- 1801 Jean-Baptiste Croteau

m. Marie-Victoire Auger » Marie-Julie

- 1821 Marie-Julie Croteau

m. François-Xavier Bibeau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau

m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron

m. Lazare Côté

- 1695 Marie-Madeleine Lemay m. Claude Houde » Simon

- 1735 Simon Houde m. Marie-Madeleine Morisset » Madeleine

- 1764 Madeleine Houde m. Jean-Joseph Croteau » Jean-Baptiste

- 1801 Jean-Baptiste Croteau m. Marie-Victoire Auger » Marie-Julie

- 1821 Marie-Julie Croteau m. François-Xavier Bibeau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron m. Lazare Côté

More tragedy befell Michelle. In November 1684, and still in the prime of her life, her husband Michel Lemay died at 54 years old and Michelle became a widow for the second time. Again, no cause of death is cited in the records. Still in her 30s, it was obvious that she found herself with little or no hope of providing for an abundance of 15 young lives that included a toddler, pre-adolescent children, and many teenagers.

On February 3, 1685, the courts of New France, known as the Prévôté de Québec elected guardians for all the minor children left in her care, most being from Michel Lemay’s first marriage. Michelle was to remain the legal guardian of all children for whom she was the natural mother. An inventory of the estate was prepared on February 28 by Jean Baudet and Jean Hamel who estimated its value at 444 livres, 5 sols. It would have been a paltry amount under such extenuating circumstances.

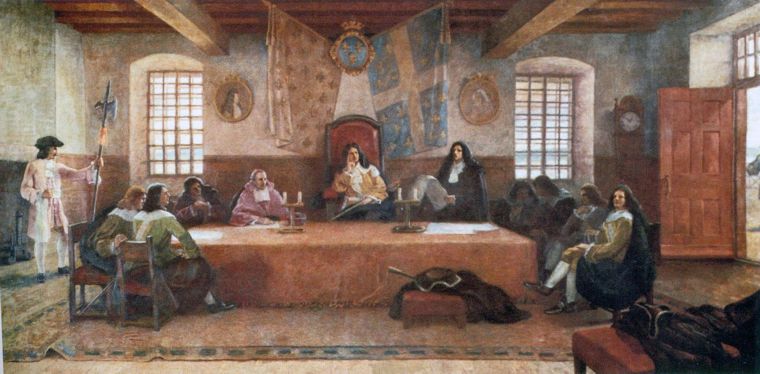

Le Conseil Souverain (sovereign council) 1663 by Charles Hout.

The Sovereign Council was the standard body for settling judicial matters in ‘New France’ in early Canada. Probably based on French European jurisprudence, the royal name ascribed to the colonial courts was Prévôté de Québec, even though the colony was not yet known as Québec.