Marguerite Hiardin

Arrived: October 2, 1665

Age at arrival: 20

Births: 9 / 6 surviving

Widowed: once

Age at death: 75

Marguerite Hiardin dite Liardin was born in France on August 30, 1645, the daughter of René Hiardin and Jeanne Serré. In her marriage contract she stated that she was from the parish of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, but the marriage register gives her birthplace as Notre-Dame in Joinville in the French province of Champagne.

It’s possible that Marguerite came from an extremely meagre background because unlike many other Filles, she listed no dowry to start her new life. All official Filles du Roi, however, had the trousseau, essentially a hope chest, granted shortly before departure by the king’s representative. Thus she would have brought everything she had of worth, and likely that was little more than her regally-issued trousseau and its contents.

Those contents presumably would help her to start a family if she met and married a nice man in New France. They were the same for every woman sent by the king — six taffeta handkerchiefs, a pair of ribbons, 100 sewing needles, a comb, a spool of white thread, a pair of stockings, a pair of gloves, a pair of scissors, two knives, one thousand pins, one bonnet, four lace braids, and two livres in silver coins. It's unclear whether those specific contents were provided before departure or after reaching Canada. Regardless, upon landing they received further items from the king's warehouse, clothing that would help them to survive the elements: two dresses, two petticoats, a morning jacket, six head dresses and various other head coverings, one muff and two pairs of sheepskin gloves.

The trousseau

The Filles du Roi were each given a trousseau by King Louis XIV's agents. This original, on display in an Ottawa museum, may be the only one that remains. (Photo by Harry Foster)

The king’s agents also made a disbursement to each girl upon leaving France of 100 livres for travel expenses broken down as follows: 10 livres for personal moving expenses, 30 livres for clothing, and 60 livres to cover the cost of passage from her original home to the port of departure, either La Rochelle or Dieppe. For Marguerite it was the latter.

Once ships that brought King Louis XIV’s so-called “daughters” from France concluded their gruelling voyages westward across the Atlantic, they made three stops along the St. Lawrence River where the Filles were received at either Québec City, Trois Rivières, or the final destination in Montreal. Considering the harshness of the voyages and the length of time it took to cross a vast ocean, it’s not surprising that most were anxious to disembark at the first port.

In 1665 Marguerite arrived in Québec City aboard Le Saint-Jean-Baptiste, almost certainly having spent her 20th birthday at sea. This appears to be the same vessel and the same trip that brought our ancestor Perrette Vallée, who likewise had a birthday at some point mid-voyage. Regardless of any apprehension Marguerite might have had about what lay ahead, she certainly must have known there was no turning back.

A sailor, Nicolas Vérieu dit Labécasse was born about 1637 in Dieppe, Normandy. His parents were Nicolas Vérieu (or Vérieul) and Perrette Roussel. Gagné in his book states that Nicolas “was confirmed 02 February 1660 at Château-Richer,” but there is nothing more to define what that means, whether referring to the Catholic sacrament of confirmation or to a record of his presence in Canada at that time. Nothing in the records appears to provide detail about his departure from France to relocate in Canada, but as a sailor it is likely he worked aboard vessels that connected Europe with Québec and he merely chose to stay. Given the poor economics of Europe, it's not hard to imagine that ambitious young men would relish the possibility of owning land in N. America, especially if there was no cost in getting there.

As it is with every single one of our Filles du Roi grandmothers, we know little about their precise meetings with their husbands, probably because there were no diaries. Seldom could early Canadians read or write. But the vetting process that occurred when men came to the Ursuline sisters to meet prospective wives is fairly well documented. We know that the sisters allowed visits on three specific days each week. We also know that the Ursulines pre-screened the women by separating them in rooms where the men they deemed most suitable for specific girls would be sent for initial meetings. Each girl would ask questions of any man based on criteria she developed upon the concerns of the nuns who watchfully stood by.

Any discussions between these women and the men they chose, the dreams they must have shared, and their inevitable romances — all of it, unfortunately, is left entirely to our imaginations. In every single case, history only picks up the trail of their lifelong commitments at the writing of their marital contracts, the equivalent of engagement in modern terms. This was the legal document of the day that would bind a man and woman, always notarized and witnessed. A separate social ceremony would follow, and not necessarily on the same day. It was only after the consummation of their marriage the king's representatives would award his final gift of 50 livres in kind to help young couples get started.

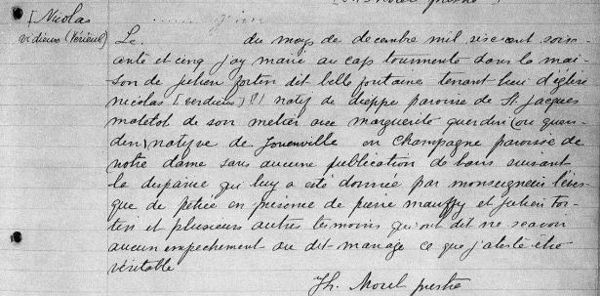

Original record of the marriage of Marguerite Hiardin and Nicolas Vérieu.

On October 5, 1665, notary Claude Aubert drew up such a marriage contract between 20-year-old Marguerite Hiardin and 33-year-old Nicolas Vérieu at the home of Julien Fortin dit Bellefontaine at Cap Tourmente, Québec. Marguerite wasn’t able to sign the contract, but Nicolas was, or at least he fashioned a signature. In fact very few people in those days were literate enough to sign their names, but we must not equate this with intelligence since illiteracy was the norm for most earthlings in the 1600s. The public marriage of Marguerite and Nicolas took place in December 1665 at Château-Richer.

While it's plausible that Nicolas continued his work as a sailor, it's more likely that he took up farming since agricultural pursuits were the livelihood of most colonists. Baptismal records from Château-Richer, Beaupré and Québec City document their children over the years that followed — nine in total — from 1667 to 1688, a span of just over 11 years. Three did not survive childhood, but the remaining six appear in the archives with their own subsequent marriages and children.

It was their second child, Marguerite Vérieu, whose lines carried her mother’s blood onward to ours through Clarice Bergeron, with not one but two of her grandchildren and two unique paths:

- 1690 Marguerite Vérieu

m. Jacques Baudon » Jacques [Jr]

- 1713 Jacques Baudon [Jr]

m. Françoise Buteau » Marguerite*

- 1751 Marguerite Baudon

m. Jean-Baptiste Bibeau » Pierre

- 1784 Pierre Bibeau

m. Marie-Josephte Houde » François-Xavier

- 1821 François-Xavier Bibeau

m. Marie-Julie Croteau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau

m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron

m. Lazare Côté

- 1690 Marguerite Vérieu m. Jacques Baudon » Jacques [Jr]

- 1713 Jacques Baudon [Jr] m. Françoise Buteau » Marguerite*

- 1751 Marguerite Baudon m. Jean-Baptiste Bibeau » Pierre

- 1784 Pierre Bibeau m. Marie-Josephte Houde » François-Xavier

- 1821 François-Xavier Bibeau m. Marie-Julie Croteau » Lucie-Marie

- 1847 Lucie-Marie Bibeau m. Alfred Bergeron » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron m. Lazare Côté

- 1690 Marguerite Vérieu

m. Jacques Baudon » Jacques [Jr]

- 1713 Jacques Baudon [Jr]

m. Françoise Buteau » Genevieve*

- 1743 Genevieve Baudon

m. Ignace Baron » Josephte

- 1771 Josephte Baron

m. Alexis Genest » Alexis [Jr]

- 1795 Alexis Genest [Jr]

m. Charlotte Aubin » Louise

- 1826 Louise Genest

m. Antoine Bergeron » Alfred

- 1847 Alfred Bergeron

m. Lucie-Marie Bibeau » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron

m. Lazare Côté

- 1690 Marguerite Vérieu m. Jacques Baudon » Jacques [Jr]

- 1713 Jacques Baudon [Jr] m. Françoise Buteau » Genevieve*

- 1743 Genevieve Baudon m. Ignace Baron » Josephte

- 1771 Josephte Baron m. Alexis Genest » Alexis [Jr]

- 1795 Alexis Genest [Jr] m. Charlotte Aubin » Louise

- 1826 Louise Genest m. Antoine Bergeron » Alfred

- 1847 Alfred Bergeron m. Lucie-Marie Bibeau » Clarice

- 1870 Clarice Bergeron m. Lazare Côté