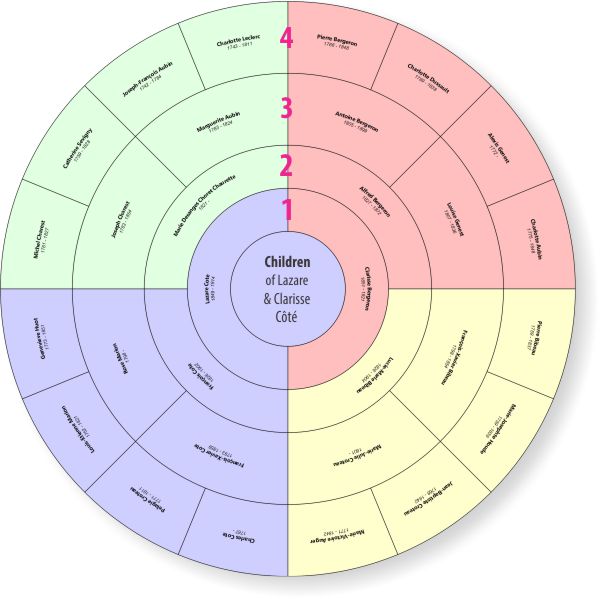

The family tree

This smaller version of the Lazare/Clarice Côté family tree was created for this website to illustrate the points I made on the genealogy page. To keep names legible, this tree contains just five generations going back to the mid-1700s. That’s unfortunate because our story actually begins when Canada was in its first wave of settlement by Europeans 100 years earlier. The 18 Filles du Roi who were among our original Canadian ancestors arrived in the small window between 1665 and 1671 in the seventh and eighth generations as you count upward, or more accurately, in the first or second generations counting downward since the introduction of Côté blood in what was to become Canada.

By the way, do not expect to be related to people today who have the same surnames as our Filles matrons. Remember, they all took their husbands’ names upon marriage. Technically speaking, of course, we are distantly related to people with their surnames provided they descended paternally and explicitly from their ancestors back in France.

This is the 'lite' version of the family tree, containing just four generations above Lazare and Clarice Côté’s children. Note that the number of grandparents quadruples in each ring. Our Filles du Roi are actually in the seventh and eighth generations, but a poster-sized page is needed to reproduce those exponential layers.

One day soon we hope to put the finishing touches on a full-sized tree containing 10 generations. We'll notify everyone on the mailing list when it's ready to download (at no charge).

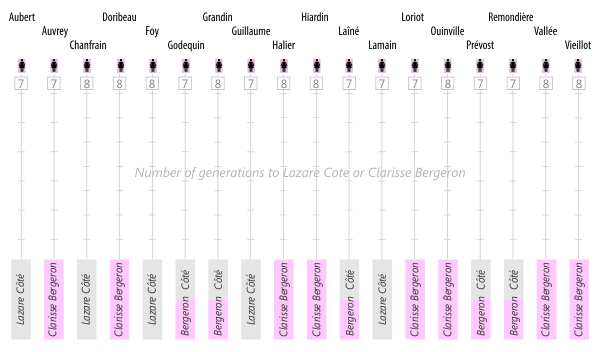

Why are 18 Filles du Roi ancestors of the Côté children and not of the parents? Because only some of those Filles are ancestors of Lazare Côté and some are ancestors of Clarice Bergeron. A few are ancestors of both Lazare and Clarice, arriving through different genealogical paths. For Lazare’s and Clarice’s children, the combined number is 18.