The hard lives led by our Filles ancestors

Never, ever think that our own lives are hard.

Not a single person in all humanity was any more a product of Canada’s founding Québécois than Lazare Côté or Clarice Bergeron. But their children and grandchildren are not sole descendants of the French settlers to whom we are indebted. Obviously there are now people spread across the entire planet whose family trees map back to the same historic grandparents. I may be one of the few who have begun to reflect on them and the sacrifices they made that led to our lives today. I hope many more people will reflect on all of this in years to come.

My fascination with our 17th century ancestors is not with their pedigrees or social standings. Nor is it with their artistry, their intellects, contributions to humanity, or great leadership. Even if they had all of that, little remains of their history to prove it. Like the majority of their countrymen back in France, they were remarkably illiterate, regardless that they might have been explicitly brilliant.

My respect comes from a different reason: their sheer quest to survive, to build a new land, and the courage it must have taken to attempt it all with so little.

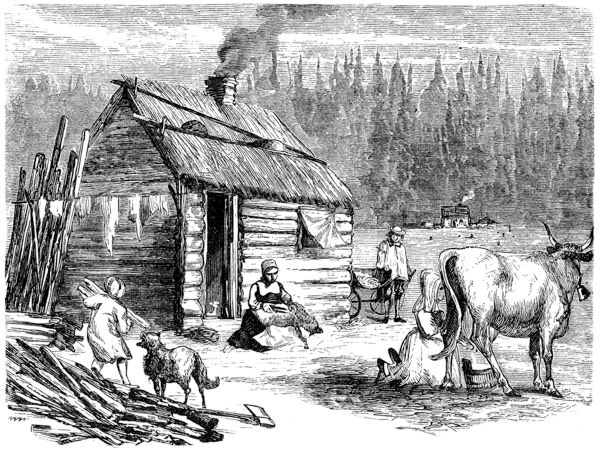

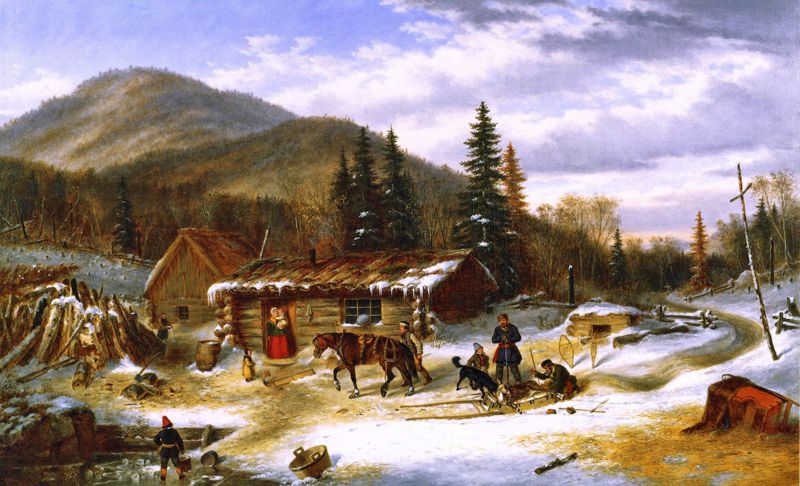

Many paintings that depict New France (Québec) in a pretty light were created centuries later and often depict the 1700s, not the 1600s. This one overlooks the onerous physical sacrifices that actually transpired in transforming a rugged wilderness into the picture it became in later centuries.

In an earlier chapter I discussed the untruthfulness of paintings from the 19th and 20th centuries. Let’s not forget the 1700s, a hundred years after the end of the Filles’ migration to Canada. Since photography wouldn’t be invented for another few centuries, artists of the day sketched and painted the lives of the New France settlers according to their own lively imaginations. Their works were fairly romantic depictions that easily overstated reality because Québec was already a century old. What these works completely belie is that the land of the first settlers was sheer wilderness. It was neither groomed nor garnished with neat farmhouses, livestock, maple trees, straight, uniform fences, nor any semblance of tidiness and prosperity. These paintings which abound today simply don't tell the true story of the land where the Filles du Roi and other brave habitants had lived and died a hundred years earlier, when a labourer with at least six children, and often 10 or more — and a wife who was usually pregnant — had neither time for such pretty decadence nor the money it would have taken.

Like almost any of Canada’s first settlers, these women and their husbands paid with every cell in their bodies to give us the lives we enjoy today. And their sacrifices were much, much greater than those of immigrants who arrived in later centuries — special emphasis on those arriving now by the millions to claim this land as their own. That our European ancestors built Canada with sweat and pain, and with enormous spirituality, simply cannot be ignored. Everyone needs to understand that.

"Vue de Chateau-Richer du cap Tourmente et de la pointe orientale de l'Île d'Orléans" is descriptive because it portrays the exact geographical area where many of our Filles ancestors settled on the banks of the St. Lawrence. This particular painting by Thomas Davies, however, characterizes the area in 1787, more than a hundred years later.

In Québec the Europeans turned unproductive forests into great tracts of agriculture that began taking the New World to a new level. In fact the ingenuity of Europeans across the continent and their determination to improve everything they touched led to the greatest of innovations — automobiles, telecommunications, medicine, photography, air travel, and practically every infinitesimal object that surrounds us in modern existence.

As I stated earlier, almost all of the 18 Filles in our family spent years under contract as domestic labourers — slaves if you like — clearing land and carrying out the agricultural pursuits of their landlords. The records also show that many or most eventually became habitants themselves when they completed their contracts and were able to purchase their own plots — a privilege that certainly did not make their lives easier.

Imagine: Nothing we have today even existed.

Many accounts written by non-historians about Québec’s habitants reflect a reasonably good life with abundant food and shelter, tools, and furniture from France, and most of life’s necessities. But I must say it again: Most of these were written in the 20th century and refer to a time very long after the Filles du Roi had come and gone. What seems ignored in the history was the quality of life for the original settlers in the 1600s, when only a few ships per year brought supplies.

Like the common table fork, factory made kitchenware didn't exist. Our ancestors simply made their own. This cooking pot (Musée Canadien de l'Histoire) typifies the state of the art, and remember that every such item would have been completely subject to rust.

Essentially when a newlywed couple began their married lives they had — well, nothing. If they weren’t lucky enough to have the use of a small cabin under a work arrangement with a landowner, they would fell trees and construct a home of logs. They fashioned ovens from rocks, a crucial component since besides cooking, it would keep them from freezing to death. Maybe. They devoted many summer months to cutting firewood, all by hand, of course. They constructed crude cookware and tools, and they sewed all their clothing. They built their dwellings close to a water source where they could chop a hole in the ice and haul buckets of water indoors. Since bacteria was only in the throes of discovery and wouldn't be understood for another hundred years, people consumed contaminated food and water on a daily basis. Obviously our forefathers and mothers took camping to unimaginable levels. Little wonder that in our family alone there were about 850* non-surviving children in the two generations that included the Filles du Roi.

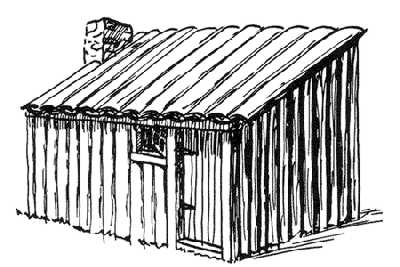

This concept of a settler's home is probably an accurate portrayal of the setting for our ancestors in the 1600s. Glass windows were only invented late in the century, so typically habitants closed windows with oiled animal skins. (Source unknown)

I have tried to grasp the inconvenience of life and survival for these people. Ultimately I could only consider what they didn’t have. Ignoring all the cliché things stemming from cars, electricity, and computers, here are other critical items that simply did NOT exist when our ancestors carved out an existence in the rugged Québec wilderness. Please note that none of these had been invented except for glass, which was new but not available for window panes anywhere in the world until the late century.

These did not exist

- lanterns, or any type of light bulb

- means of refrigeration

- stretchables (clothing, hair bands, etc.)

- glass windows, glass anything

- pencils or instant writing devices

- cardboard, plywood

- thermometer or any means to know temperature

- shampoo, bleach, peroxide, or detergents

- common bandages, adhesive tape

- ability to tell the time at home

- septic tanks

- knowledge of the existence of bacteria

- screw-on lids or caps of any kind

- bathtubs

- left and right shoes

- plastic, rubber, or silicon (thus thousands of items we rely on today)

- bicycles

- insulation

- table forks

- zippers, snaps, hooks, safety pins

- nylon or any other synthetic product

- toothpaste or toothbrushes (yikes!)

- hard soles on footwear

- padlocks or door locks

- tampons, menstrual pads

- food canning technology

- antibiotics or vaccines

- matches or any other easy way to make fire

- organized schooling for children

- prescription lenses or sunglasses

- metal screws or staples

- running water (not even a crude facsimile)

- toilet paper (nor the Sears catalog)

- non-rusting metal products

Our Québecois ancestors deserve to be noted for amazing things, but their breath or body odour would almost certainly not be among them. These people had a very different concept of hygiene than we do today thanks to our education and the availability of products that allow us a more hygienic world. All settlers arriving from Europe, men and women alike, essentially brought a culture that extended from the middle ages. They wiped their bottoms with a communal rag on a stick where it would be reused by the next person. Toothbrushes would not appear on the scene for another hundred years, and handwashing or body bathing was rare, likely because of the added burden it would place on survival in what was already a very inconvenient world.

Theirs were also lives of silly notions. Today we might regard these as a mixture of ignorance, superstition, and antiquated religious quirks. For example, these people actually believed that hot or boiling water brought illness; it did not prevent it. Or that inhaling the smoke from tobacco was a good thing.

For many, survival in Québec’s unfriendly winters meant knowing how to face mornings in small, frozen log cabins in a single room full of hungry kids. Some accounts note that they defecated indoors in metal or wooden buckets. Newborns were born in the same room, often on the floor to prevent soiling the family bed. And they often died, as the biographies in the next section make clear. Primitive tools and clothing were heavy and completely useless when wet. There were rarely neighbours passing by to ensure their well-being or to make connection with the outside world. The only roads were coarse trails worn into the snow by the feet of humans and animals. These people had to be prepared. They suffered direly if they weren’t.

Early colonists needed shelter. This sketch typifies a first dwelling that might have been constructed by a young family, including those of our Filles du Roi ancestors. It was usually a single room and contained a stone fireplace on one end. © Boréal Express

In fact for most settlers in early New France, daily life was a ritual of brutally hard work. Pregnant or not, when women were not helping their husbands to fell trees or perform other heavy tasks, they were sewing all the family’s clothing, growing and collecting food, and attending to the needs of many children — our Filles ancestors bore many, as you already know.

Men were likewise overwhelmed with endless, often dangerous work. The arrival of summer demanded above anything else the obligation to prepare accessible food and shelter for the arrival of winter. There was no protection from biting insects, outside or inside the home. Lice, bedbugs, typhus, and purple fever were rampant. And if a man’s axe slipped and dealt a serious injury to his leg, it usually meant the end of his life in an age where antibiotics did not exist.

In the biographies I state over and over that very few causes of death exist in the records. I wrote this so often that I grew tired of saying it. We can only guess that the reasons people died were simply unknown and thus irrelevant at that point in history. To further muddy the data, any diagnoses by doctors of the day were probably quite inaccurate. It would not be imaginary to say that deaths were almost certainly the consequence of injury, of freezing, of pneumonia, or of infectious disease, because in those days, death was seldom from truly natural causes. Very few people in the 16th and 17th centuries actually lived long enough to die from cancer as we know it today. And their deaths must have often been excruciatingly painful, drawn out, and without much dignity. We are so much luckier, and I defy anyone to say that we do not take our good fortunes for granted.

While his work depicts New France in later years, few other artists appear to have described the culture more than Dutch-born Cornelius Krieghoff in the 1800s. Regardless of a few visible improvements in construction and utilities of the habitants he portrays, it's not hard to imagine the correlation of his vision to lives of the Filles du Roi during the 1600s.

In spite of the dreary picture I paint, it is a fascinating fact that the average lifespan of our own 18 Filles ancestors (but not the entire coterie of Filles) was about 59.75 years. They outlived the statistical norm in New France by nearly 50%, since age 40 was the average longevity for early colonists stated by demographers, a number undoubtedly affected by the early deaths of men whose livelihoods were steeped in peril. There were only two of our Filles for whom we know the cause of their premature deaths, that is, the two who died in childbirth, Perrette Vallée and Renée Chanfrain. Almost all others died at ages that well surpassed the 40-year average. We also know that 13 of our 18 Filles ancestors were widowed at least once. Three of those were widowed twice! This might be evidence that bearing many children and living in a non-industrialized, remote environment actually increases female longevity.

"French Canadians enjoying a dance", a painting by Henry Sandham in the late 1800s.